Don't quite understand the beginning of your post but you are very welcome all the same. I was inspired by the Masterplan, to do what I could to remind people of the history of the Park, no idea if that has been achieved.

As the Masterplan arose form the Sports Council announcing they were abandoning the Sports Centre, and in anticipation of its demolition, I can understand the desire to make more public space, and emphasise the history that was obscured when the sports centre was built. As it is now listed and won't be demolished, I don't understand how they can still insist on building on the Rockhills site, when while a little bit of land will be lost, but nothing can really be added to the publicly accessible part of the park.

An image of the park with many of the temporary buildings of the Festival of Empire 1911 [some stood for 50 years] was used to indicate [in a recent thread] that the park is not land without a history of building. Mmm? I'm not sure it's really relevant. It was originally common land as Penge Common, when it was sold to the Crystal Palace Company, it was then the private property of Leo Schuster. The Palace and the Park were a private concern till it was sold to Lord Plymouth. If he had not bought it, it could have been bought by anyone to build housing and current arguments would never take place. Lord Plymouth was repaid what he spent on it, but it remained a place where admission needed to be paid before entrance, bar the area near the Penge entrance. It was closed again during the Second World War, and took sometime to reopen fully. I can't see what any stage of the Palace's history sets precedent for or against development or public access. How about we just let ourselves have what we want, grass, butterfly houses or blocks of flats.

In this spirit, here's a comtemporary article, showing an example of an 1911 Masterplan - The Festival of Empire. A reminder perhaps of a time whenthat if you were struggling to make a success of your life here in Britain, you could always just leave.

I'll add the illustrations when I find my scanner.

THE FESTIVAL OF EMPIRE

BRITANNIA’S UNIVERSAL PAGEANT.

BY ALLIN GREEN.

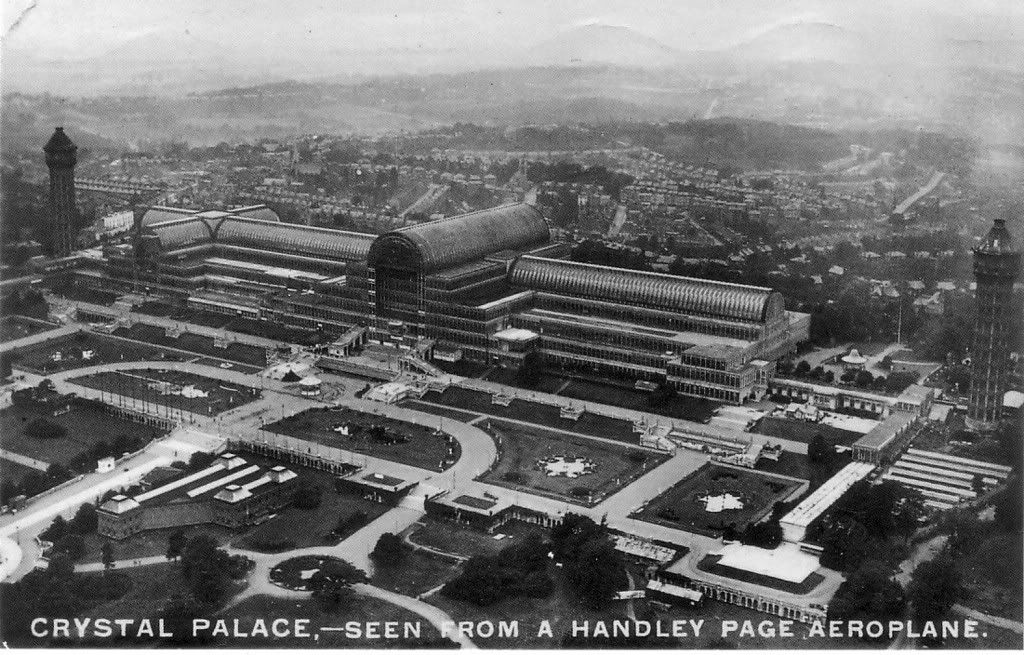

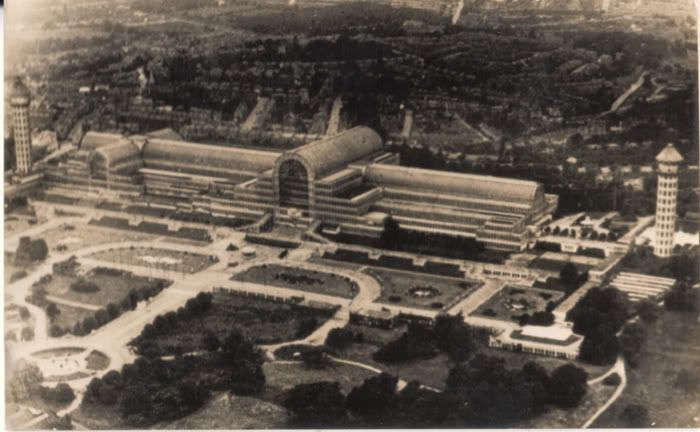

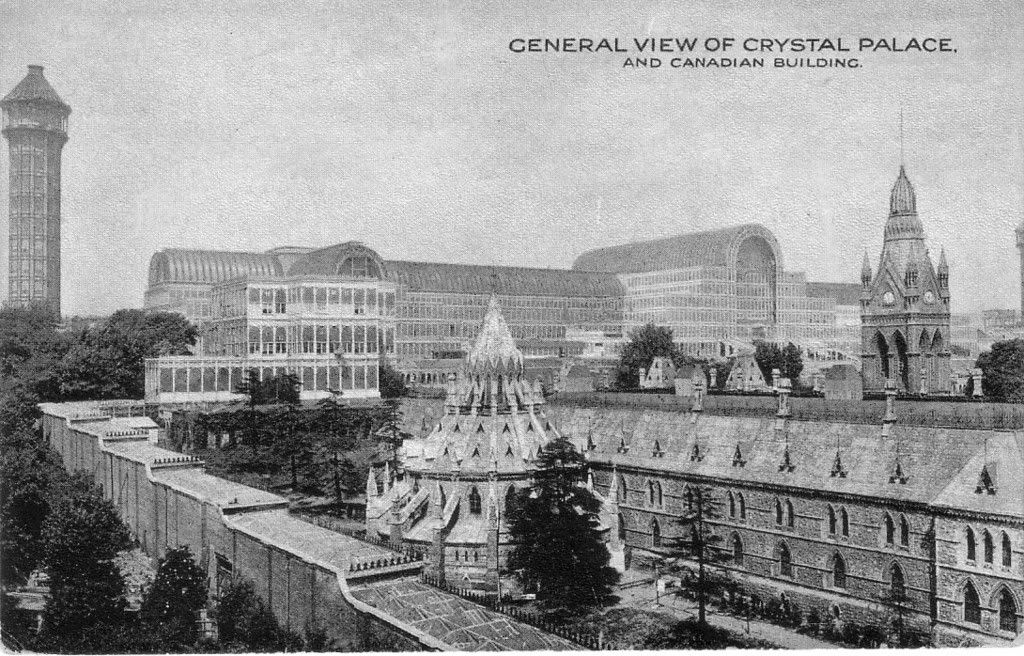

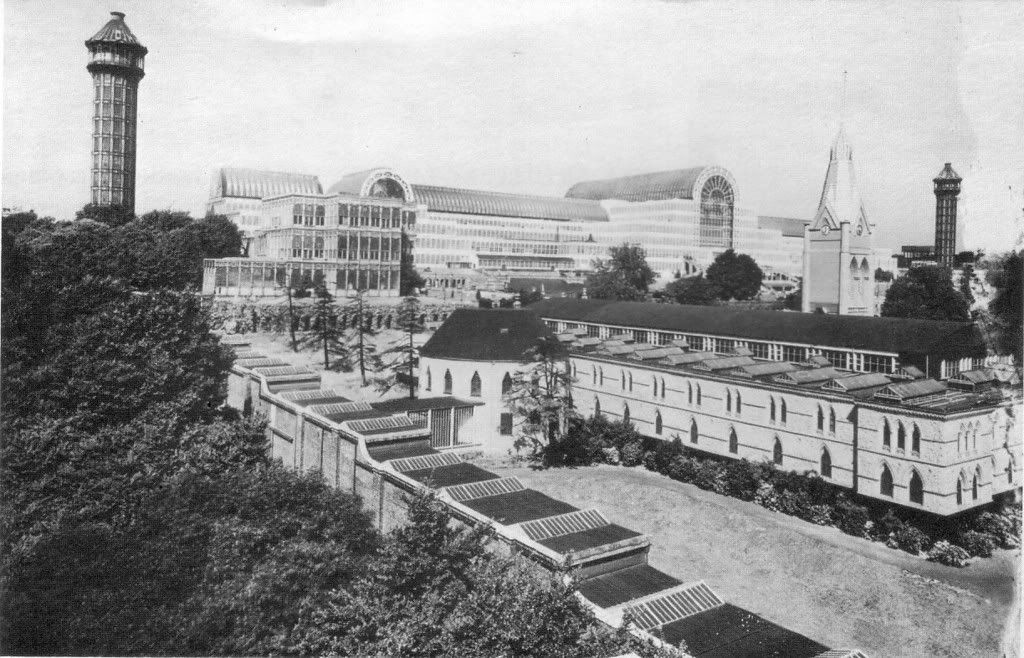

THE picturesque slopes of Sydenham have more than resumed their Victorian animation. Today the Crystal Palace and its two hundred and fifty acres of grounds holds the largest, most ambitious, and most up-to-date series of exhibitions that our mighty Empire has ever known. Incidentally, one may wonder whether this Imperial hustle, this shop-window of John Bull, Unlimited, will result in the Crystal Palace becoming more the people’s playground. The public, in these strenuous days – days wherein we play hard as well as work hard – declines to find entertainment in statue-adorned gardens alone. It wants something stronger, something to take its attention by storm, something which thrills and fascinates as well as pleases in a mild way. The Crystal Palace, originally constructed in Hyde Park, by Sir Joseph Paxton, for the great Exhibition of 1851 – the British boom organised by the Prince Consort – is still the most remarkable building of its kind – an engineering marvel – and it has been left to the Council of the Festival of Empire to demonstrate what enterprise, influence, and money can do. In place of but occasionally frequented lawns, the Festival of Empire has given us some three hundred ornate buildings, ranging from the seventy thousand pounds palace of the Canadian Government to charming kiosks. Disused water towers have been cast upon the scrap heap; moss-grown cascades, long innocent of plashing water, have provided sites for the pavilions of Australia and New Zealand; faded bandstands have been whisked away; statues, interesting as works of art, but not calculated to enthuse the tripper, have been stored in some suitable gallery; clumps of bushes have been cut through to make way for the All-Red Route : hills have been levelled, and dells filled in. In short, on the site of this playground of the past has risen a pleasure-ground of the present – a noble feature among the Coronation landmarks of King George V., the first monarch who has visited every portion of his far-flung dominions here represented.

And yet, while half a million of money has, during the past nine months, been laid out, upon buildings, railways, amusements, roads, paths, stairways, grandstands, illuminations, and so forth, the rural charm of the Palace parkland has not been damaged. No vandal hand has been laid upon this fair scene, for the head of this notable illustration of the Empire is the Earl of Plymouth, well known for his taste and judgement as an art critic and patron. Indeed, with the utmost truth it can be stated that while the Crystal Palace has been utterly transformed this year, it is an infinitely more delightful resort than ever. Not a tree of any value has been sacrificed. Expert gardeners – gentlemen who have made a study of horticulture and floriculture – have watched the changes, in order that the natural charm of the grounds should not be destroyed, while, with the aid of many thousands of plants, shrubs, rose trees, pergolas, loggias, terrace-gardens, water-gardens, and so on, the eye is even more enchanted than formerly.

In order that the grass-lands should not be disturbed more than was absolutely necessary, workmen were expressly forbidden to go off the roads and paths unless their duties compelled them to. Even before a holly bush was removed, the permission of the chief gardener had to be obtained. One day, in February, this functionary was going his rounds, when, to his horror, he espied a fallen sapling. Indignantly he demanded of the only toiler near the spot why the young birch had been dug up. “Sure, sorr, and no one dug it up,” replied the Irish foreman. “Then how comes it to be lying on the earth ?” “It just fell down, sorr, of uts own accord.” “But who dared dig so close to its roots as to make it fall ?” “ I don’t know the man’s name, sorr,” replied the diplomatic son of Erin, “but he’s gone to work in another part of the ground.” And, realising that pat was too good a witness to commit himself under cross-examination, the tree treasurer turned away with an amused smile.

In many ways the Festival of Empire is a noteworthy effort. To begin with, it is, after the Coronation itself, the outstanding event of this historical season – a season which is making London the holiday sity of the universe. Again, this is probably the first great exhibition formed before our very eyes. There was no closing of gates, no evolution in secrecy, no shutting out of the public. Never once have the gates of the Palace or of the park been closed to the people ; all were free to roam where they listed, and to observe everything which was being done for their benefit.

Then, for the first time in sixty years, His majesty’s government has lent its patronage to an exhibition, while the Premier, Cabinet Ministers, Governors General of the Overseas Dominions, and other men in high official places are vice-presidents of the Festival.

But most remarkable of all is the unique fact that this vast organisation, rendered possible only by the guaranteeing of nearly five hundred thousand pounds, has been done without the slightest hope of personal profit. No syndicate or promoter will swell a bank balance as a result of the Festival of Empire, for all profits are to be given to the King Edward VII. Hospital Fund. The past can show no parallel to this patriotic, imperial, and philanthropic series of exhibitions.

http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/about_us/our_history.html

How came this mammoth machine to be started ? For years it has been the dream of artist organisers to hold a pageant of Empire – to relate, by means of a living history book, the story of how this mighty assemblage of lands came beneath the sway of the vigorous Anglo-Saxon, and then grew into our present Empire. Over and over again, since pageantry was revived in many a centre of localised history, have attempts been made to create a pageant which should be remembered as something of national and imperial importance,.

Several season ago, Mr. Frank lascelles, the designer of glittering pageants at Oxford, Bath, Quebec, and Cape town, thought out schemes by which, with the aid of fifteen thousand voluntary performers and several thousands of pound’s worth of costumes, arms, scenery, and properties, the tale of Britain could be told from the prehistoric times when London was a collection of mud huts on the banks of the River Fleet to the time when our present King opened the first Commonwealth Parliament of Australia.

http://thesibfords.org.uk/sibipedia/frank-lascelles

With the active support if the Earl of Plymouth and other distinguished men, Mr. Lascelles gradually evolved his plans, until, early in May of last year, all was ready, from Sir Aston Webb’s huge amphitheatre down to the smallest detail. Then, within a few days of the long – expected opening, came the passing of Edward the Peacemaker. To have held a gay and gorgeous Festival of empire when all the Empire mourned was unthinkable. It was, therefore, a deeply-depressed little party which stood on the Grand Terrace of the Crystal Palace and gazed upon the wasted work. Artists every one of them, the lieutenants of Mr. Lascelles were sad of heart to drop their hands at the moment when the realisation of their conscientious labours.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aston_Webb

Then came a ray of hope over the darkened scene. “Now we mourn the loss of King Edward. Next year we shall rejoice at the crowning of King George. Next year – “ said one of the party, and he left the rest to imagination. So he struck the keynote of hope, and others, thus inspired, added their quota. Said one: “Let us have an even more expansive pageant, to take in episodes from far-off lands where flies the Union Jack.” Said another : “Let us raise on these very slopes a series of scenes of life in all parts of the Empire.” Said a third : “Let us show the art and industry of Britons by holding in the Palace itself a comprehensive display of all-British goods and methods of manufacture.”

So the Festival of Empire, the Pageant of London, and the All-British Exhibition grew. Lord Plymouth was able to form a brilliant council of ladies and gentlemen in whom the public have every faith. H.R.H. the Princess Louise, The Dukes of Norfolk, Devonshire, Marlborough, Westminster, and Fife, and many other noblemen, came to his aid, while the support was enlisted of such influential people as High Commissioners of Colonies, the Churches, the President of the Royal Academy, captains of industry, chairmen of chambers of commerce, lord mayors and representatives of the fine arts, the Law, the Army and Navy, and may public bodies.

Further, the Festival, which has brought together an extremely able body of administrators, was most fortunate to secure, as its Honorary Secretary, Mr. A. E. Forbes Dennis [Alban Ernan Forbes Dennis], and as its surveyor, architect and business manager, Mr. Herbert W. Matthews, and as its chief painter and inventor of amazing scenic effects, Mr. Leolyn G. Hart, who, with nearly a hundred brothers of the brush, has turned out many miles of painted canvas for the All-Red Route – a ninety thousand pound’s realisation of Empire.

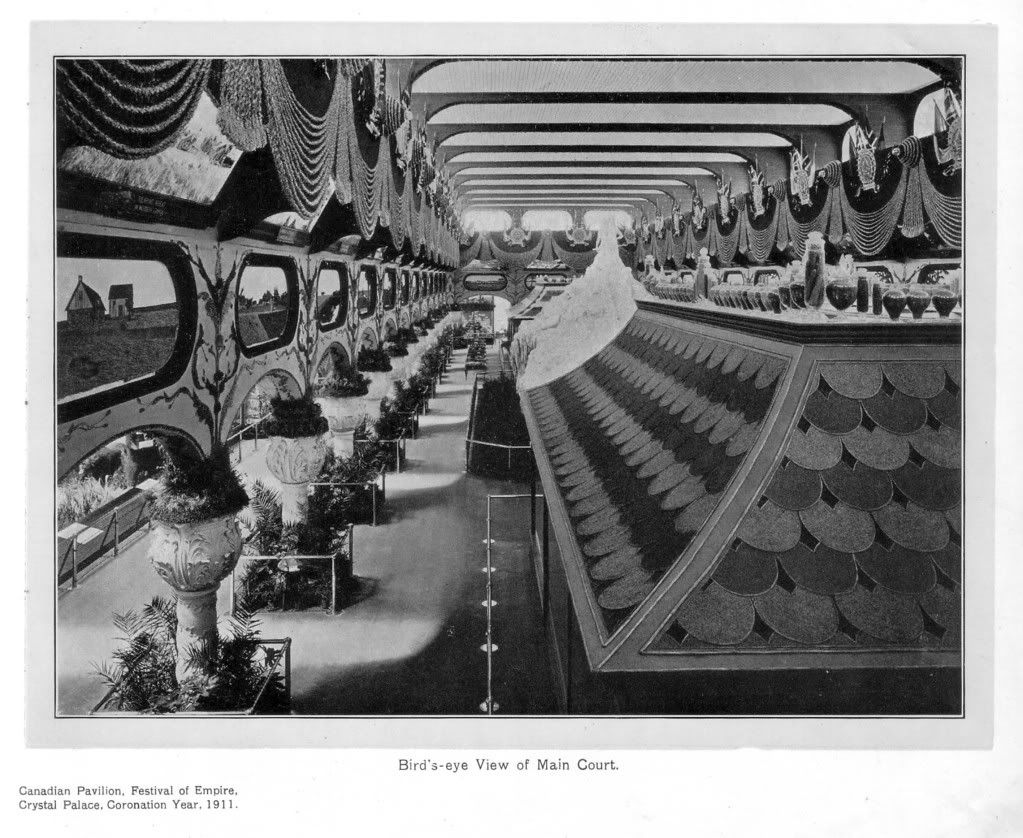

That this expression of what Empire means appealed to those go-ahead brethren of ours on the other side of the Atlantic may be judged from the fact that the Canadian Government at once voted seventy thousand pounds for the erection and equipment of a great palace in the grounds. This building, the finest ever erected as a temporary show place, is two-thirds size actual reproduction of the Parliament building in Ottawa. The enormous pavilions of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Newfoundland are also exact replicas of Government offices in the various dominions, while the Indian building, where is stored a priceless collection from our Empire of the East, is a copy of the Taj Mahal at Agra.

Even those who have been most closely associated with the growth of the Festival can hardly realise the limitless enterprise of the many departments which had their headquarters in fifty rooms at Empire House, Piccadilly. What a stroke of genius it was to create that remarkable advertisement in being – the gigantic model of the grounds and buildings which is shown in a specially-erected pavilion in Aldwych and Strand ! It has added a thousandfold to the interest taken in the Festival by “the man in the street.”

Difficulties arose time after time, as they were bound to, but all were overcome with inspiring energy. When it was pointed out that the Crystal Palace was a long way from town, the London Brighton and South Coast Railway agreed to electrify the line from Victoria and London Bridge, so that the journey could be accomplished in fifteen minutes.

When it was found that large crowds of people could not flow rapidly and comfortably in and out of the Palace, the Council decided to construct two wide and finely-proprtioned flights of stone stairways from the level of the Palace floor to the main terrace.

Think, too, what it meant to repaint the great glass house, to clean over a million windows of five feet in length each, to lay down a mile and a half of electric railway in the grounds, to prepare ten miles of roads and paths, to bed out three million plants and shrubs, to fix twenty miles of electric lamps, to lay three additional miles of water-pipes, to put in three thousand horse-power of machinery in one power station, to hang twenty-five thousand yards of calico awning in the Palace roof, to place a million feet of other drapery round the sides, to buy twenty historic old State coaches, and a thousand horses and cattle for the Pageant, to make fifteen thousand costumes and suits of armour !

So one might go on enumerating the details of the work that has gone to the making of the Festival. Suffice it to say that with such thoroughness was the herculean task taken in hand, that British manufacturers flocked in to support the Empire’s unique display. In fact, quite early in the period of preparation the demand for space in the Palace and in the Canadian building was so heavy that intending exhibitors had to set about constructing their own pavilions in the grounds.

From the first it was intended that the All-British display should not be a dry goods affair, but that, wherever possible, the exhibits should consist of working models. Nothing seems to have been forgotten, from the raising of new restaurants to the provision of Empire sports, in which teams of athletes from our Overseas Dominions will participate.

A glance at a few of the exhibits gives one an idea of the desire to delight crowds of visitors. As one wanders about this spreading show, one sees nearly two million pounds worth of dazzling diamonds from the Kimberley mines, pictures from the Duke of Marlborough’s galleries at Blenheim Palace, fifty thousand pounds’ worth of old English porcelain and other curios, photographs from the cleverest operators in all corners of the earth, hats being made from the fur to the finished article, a stage whereon the latest fashions of the day are worn by beautiful English girls, battleships to demonstrate how the Thunderer was built, an entire street of Tudor houses, a stone reproduction of the Temple of Minerva at Bath, an appliance for cleaning boots by electricity, a cinematograph theatre where only living pictures of the Empire are cast upon the screen, a gold mine in full working order, a jungle where lurk the wild animals of India, a guess at the London of A.D. 2000, a representation of bush life in Australia. In fact, the round of varied interests is longer than can be followed in the day, even if one did not step aside to watch, for a couple of hours, the army of pageant performers in the enclosure below the North Tower.

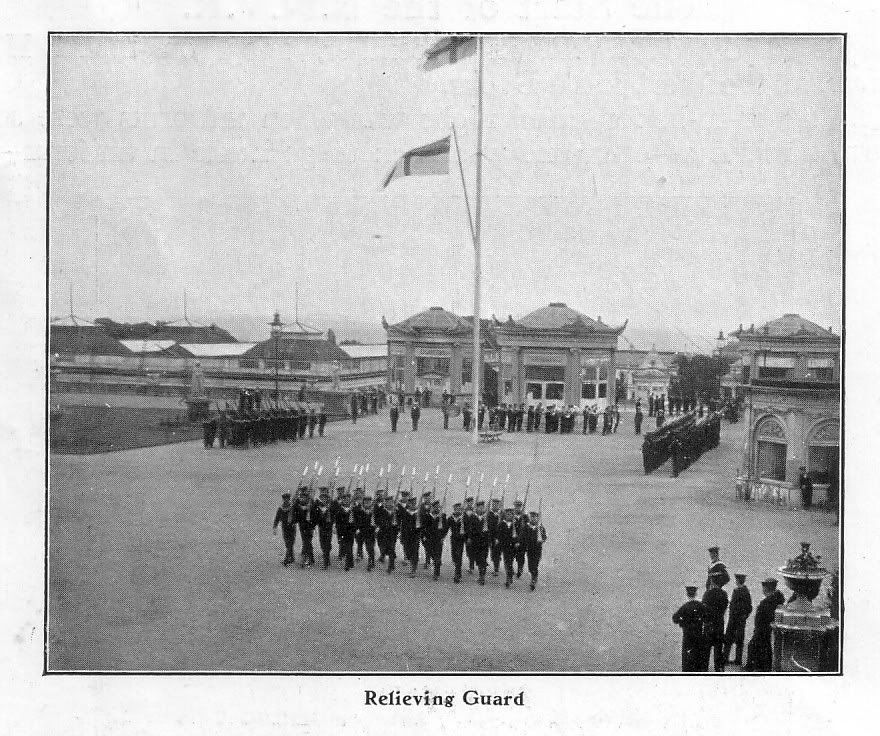

Again, the energy of the Festival founders has found outlets in the arranging of carnivals, battles of flowers, tattoos, naval and military tournaments, flower shows, Boy Scouts’ camps, an exhibition of child-life, Empire and county concerts, gymnastic and physical culture displays, flying matinee performances in the Crystal Palace Theatre by leading players, championship cycle and swimming races, and tableaux of Empire.

One especially attractive and important section of the display in the grounds is that devoted to small holdings and country life.

This, conducted on eminently practical and educational lines, occupies about ten acres, and the man who has a holding, or even an allotment, learns how he may advantageously stock it, and in what market he may get the most remunerative return for the capital he has invested and the labour he has expended upon its cultivation. There is a model homestead designed on inexpensive lines for the accommodation of the small farmer and his family. Close at hand are the farm buildings, comprising stables, cow-sheds, and greenhouses.

There is likewise a model dairy, a creamery, a factory for producing cheese, an egg-collecting depot, a bacon factory, a fruit-bottling room, a bee-keeping department, and a depot for handling market garden produce, with experts in charge of each branch.

17 Small Holdings Exhibition.

In the main, the raison d’etre of this Festival of Empire is to make the stay-at-home Briton see, in the most attractive form, the significance of our self-governing possessions in all parts of the world, to show us the industries, the progress, and the unlimited possibilities of those vast possessions.

The aim is to preach the gospel of Empire, and, at the same time, to form an Imperial “At Home.” Travelling Englishmen have long declared that while they, in the Colonies, have been treated with the widest hospitality, we in the old country seldom make an effort to return that kindness. The Festival is endeavouring to alter that. For example, all visitors from overseas are especially welcomed, and the Dominions Club, established at Rockhills, the former residence of Sir Joseph Paxton, the creator of the Palace, is open to them all. There they are being received by the Hospitality committee, and from there tours of the United Kingdom are arranged.

In this and in other ways the idea of making the Festival of Empire a great “at home” for all Britons is being fostered, and that Lord Plymouth and his colleagues have struck the true and lasting Imperial note is emphasised by the fact that King George has decided to celebrate his coronation by inviting a hundred thousand school-children to spend June 30 at the Festival of Empire, when His Majesty will cause his little guests to gain a glimpse of the wonders of that world over which he wisely rules.

A £500 MODEL OF THE FESTIVAL OF EMPIRE BUILDINGS.

Photo by Gale & Polden.)

ANOTHER MODEL OF THE GENERAL SCHEME.

Photo by Russell & Sons.

A CONTRAST TO THE PRECEDING MODELS: THE MALAY VILLAGE SHOWN IN THE GROUNDS.

Photo by The London News Agency.

A MAORI TABLEAU.

Photo by

THE FEDERAL HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT, MELBOURNE, AS REPRODUCED IN THE FESTIVAL SERIES OF BUILDINGS.

Photo by Russell & Sons.

GOVENRMENT BUILDINGS, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND, AS REPRODUCED IN THE FESTIVAL SERIES OF BUILDIGNS.

GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS, ST. JOHN’S, NEWFOUNDLAND, AS REPRODUCED AMONG THE FESTIVAL BUILDINGS.

GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS, OTTAWA, AS REPRODUCED AMONG THE FESTIVAL BUILDINGS.

OLD LONDON WALL RECONSTRUCTED.

Photo by The World’s Graphic Press.

KNIGHTS TO THE TOURNAMENT

Photo by Everitt, Crystal Palace

MEDIAEVAL COURTIERS LEARNING TO BOW TO THEIR SOVEREIGN.

Photo by The World’s Graphic Press.

THE BAKERS CAR.

THE CITY OF LONDON CAR.

THE BARBER’S CAR.

Three photos by London News Agency.

GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS, CAPE TOWN, AS REPRODCUED AMONG THE FESTIVAL BUILDINGS.